Project: Synesthesia

December 3, 2012

[This was originally posted on an earlier blog of mine Linkguistics]

Recently in Hacker School, I finished a project using Python I called “Synesthesia.” The concept was devised by my housemate Natan, but it seemed to be an interesting engineering problem that would allow me to revisit my psycholinguistics knowledge. And then we can hang our art in our living room.

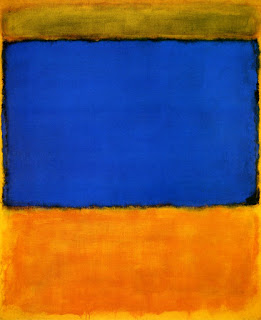

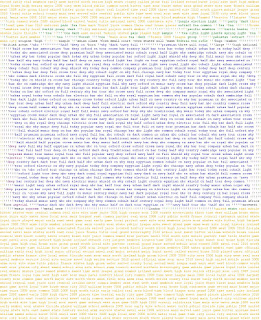

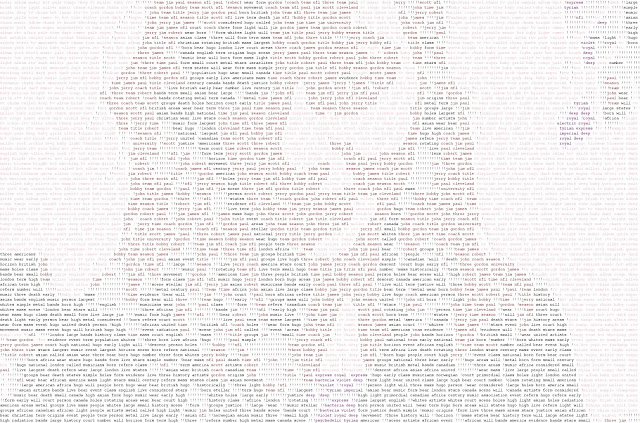

The concept: A generative art program into which you feed an image and you get back another image such that all the colored regions in the original are replaced with words that are related to that colors. So, a previously red patch might sport the words “cherry,” “communism,” and “balloon.” Here’s what happens:

This program has several parts, the logic behind each I will explain in more detail later. They are:

- Making the image’s color palette simpler based on what the user’s preferences. For the image above, I chose green, blue, orange, and black.

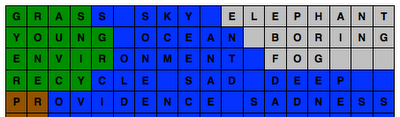

- Figuring out which words are related to those selected colors

- Putting the words where the colors are

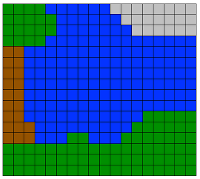

###1. Simplifying the Image: imagesimpler.py In order to best figure out what words should go where, I needed to simplify the color space of the image. So, we as humans know that the blue section in the original above is all, well, blue. However, neighboring pixels in image are a) different colors and b) defined not by their names but by the amount of red, green, and blue they comprise. This trio is called the “RGB value.”

To do this, I used a nice module called webcolors that allowed me to make a list of the RGB value for each of the colors specified by the user. Then, I calculated the Euclidean distance between each pixel in the original image and the list of RGB values I’d created. Subsequently, I replaced the pixel with its nearest approximate, creating a simplified image.

###2. Related Words: cooccurrence.py In order to get a list of words that are related with the colors in the image, I appealed to the idea that related words co-occur with one another. I created a module that will find words that co-occur with any target word. To do this, I first scraped Wikipedia articles that come up when you do a search for the target word, compiling them all into a single corpus. I did this using Beautiful Soup. Following that, I created a frequency distribution of words that occur within a certain distance of the target word within it’s scraped corpus, seeing how many times each word appeared. I then used this distribution to determine which words co-occur significantly with the target.

###3. Creating the Art: synesthesizer.py To create the “synesthesized” image, I started at the top left corner, figured out what color the pixel was and popped the first word related to that color from the list of related words, and put in a new image in the corresponding space. Each letter in the word stood in for a pixel, and each word is separated by a space, which is also a pixel. The “color” of the word is determined by the color of the pixel-space it begins on. So, if the word “cat” were placed, the next word would begin 4 pixel-spaces after “cat” began. If the next word in line for the color doesn’t fit on the line, it’s put back in the stack and I start again at the new line. I know that’s a bit confusing, so here’s a visualization:

I admit that this is a lazy approach, which both muddles the image and makes the right side of the image have a terribly jagged border. I should perhaps create a dynamic programming algorithm (it’s a knapsack-y problem) that will pick words based on which ones with fit in the amount of the color that is left.

EDIT 12/5/12:

Writing this post and having to defend all my lazy design decisions made me realize that well, I was just being lazy and I could learn so much from actually solving the problem instead of just saying “close enough.” I wanted to fill in each line of color without wasting space or running off the edge of the color’s space. Sounds like a linear packing problem to me! A month of Hacker School has passed since I made my original (lazy) design decision, and in the past month, I’ve realized that I can solve any hard problem if I just work enough at it. Even an NP-hard problem!

I paired up with another Hacker Schooler, Betsy, because two brains are better than one, and we set to making a better painting algorithm. After joking a bit about solving the bin-packing problem and then getting a Field’s medal, we decided that just making this algorithm better would be sufficient, resigning to our O(n!) fate. The way to find the most optimal solution is to find all the solutions and choose the best one.

Quite expensive yes, but we know storage is our best friend. Because the corpuses from which the co-occurrences are calculated aren’t scraped freshly every time, we realized that we could store the results from our combinatorics in a pickled dictionary keyed by color and then by length, greatly reducing the online runtime. However, we realized that we didn’t need to calculate all of the combinations. We found only all combinations that are shorter than a certain number of characters (25), realizing that anything longer than that could be recursively split into two shorter segments which would have solutions within the dictionary. Then, when filling in the images line by line, we see how long each color segment is and then pop off the next word in from the “reconstituted” dictionary. In the event that a segment of color is shorter than any of the words, we put in exclamation points as a place holder. This method allowed us to reproduce the image extremely precisely, but we are going to look into different solutions.

Another little interesting problem I’ll touch on was that there were originally vertical bands of spaces running down the entirely orange segment in the Rothko you can see as the sample image above (the orange and blue one). We realized that this was because the line was always being split in half at the same place, leading to there being a space in the same place on each line at the junctions between the spliced segments. We added a random shift from 0 to 4 when splitting longer segments so to add noise and eliminate the band. Sweet!

It’s really exciting to me now that more detailed images actually look better now than ones that are less so, like the above Rothko. Look, it’s me!

Check it all out on github